In 1899, while Orville and Wilbur Wright were turning their interests from bicycles to aeronautics, another inventor had already sketched on paper his design for a flying machine. Had Alexander L. Pepin had the money to construct his designed aeroplane then, the history of aviation might have turned out differently. Instead, Pepin would have to wait a decade to put the finishing touches on his invention under a huge tent in downtown Asbury Park, New Jersey. Even then, as he rushed to get his plane ready for the now famous Interlaken Air Show of 1910, a series of misfortunes left his plane and dreams of fame in a trail of broken parts scattered across the fairgrounds.

Alexander Louis Pepin was born July 23, 1870, in Sherbrooke, Ontario, Canada. The youngest of ten children in a family of modest means, Alexander had to begin work at an early age to help support his family. He immigrated to the United States in 1889, settling in the city of Norfolk in upstate New York. There, in 1901, he opened a clothing store which he operated for a few years before taking a job as a clerk in another store. In Norfolk, Alex married local resident Emma Bennett. Alexander’s real passion was inventing things. In 1905 he invented a game called “St. Louis Prize Winner” which he sold for $200. He also invented a new style lawn mower, a drinking fountain and a thermos-like device that could hold three different drinking liquids. For that latter, he received a U.S. Patent. Alex’s interest in flying drove him to become an experienced balloonist. And around 1904, having heard about the Wright Brothers successful flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, he quit his job and began working on his own flying machine.

In 1906, Pepin finished building his first aeroplane and displayed it on July 4 in Norfolk. From there, the plane was on exhibit in the Ogdensburg, New York, resort of Sandy Beach where it was admired by several thousand people. We don’t know if the plane ever flew that day or what happened to it after that. But, by the next year, the Pepins were living in Ithaca City, New York, and by 1908 had relocated to 1030 Sewall Avenue in Asbury Park, New Jersey. There, Alex took a job as a clerk. By 1910, Pepin had moved to 918 Munroe Avenue in Asbury Park and began working on his next airship.

Asbury Park’s founder, James A. Bradley offered a $500 prize to the first person who could make a successful flight between Asbury Park and New York City and Alex Pepin was determined to compete for it. After getting financial backing from three prominent local businessmen, Pepin started building his flying machine under a huge tent behind his 918 Munroe Avenue home. Pepin dreamed of flying his airplane over the Asbury Park boardwalk, night and day, as a huge tourist attraction.

In August 1910, the Asbury Park Aero and Motor Club sponsored the first of its kind air show at a large stretch of open land in Interlaken, just northwest of Asbury Park. They had wanted to hold it on the Asbury Park beach but that area was not large enough for the event. Billed as “America’s Greatest Air Meet,” the event offered $20,000 in prize money to the relatively few “birdmen” that existed in the United States. A grandstand was erected to seat 10,000 people. In all, over 100,000 people attended. The Wright Brothers brought their pilots and planes, one of which crashed injuring eleven spectators. The event was full of excitement, both good and tragic, including the first airmail delivered letter, the first night flight and the death of a parachutist. But local attendees were there in part to see local airman Alexander Pepin fly his machine.

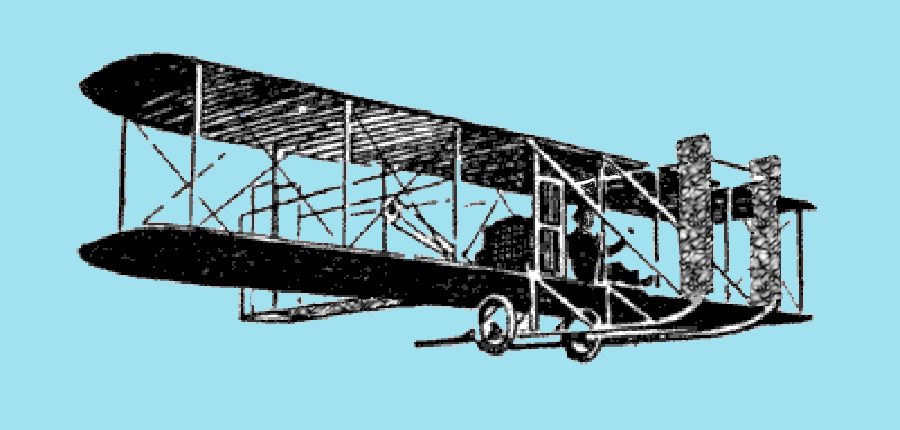

This was Pepin’s third model. The first was rejected by the patent office as too complex. The second was better but this one seemed to check all the boxes. Pepin’s flying machine, a biplane, was made of aluminum and spruce. The plane was 28 feet long and 6 feet wide, covered with rubberized musin. The control was all done by one wheel making manipulation comparatively simple. The machine had a 40-horse power motor and an eight-foot long propeller made at the local Buchanan and Smock mill. The motor and framework were completed with the help of mechanics from the Croce Automobile Works in Asbury Park. In total, the plane weight 425 pounds. Numerous aviator experts, in the city for the airshow praised Pepin’s design.

But Pepin did not appear at the airshow on the day he was scheduled. A slight accident to his machine delayed his appearance. The next day, during its initial trail at the fairgrounds, a driving rod broke and tore through the bottom of the engine and the shock cracked a cylinder head. This occurred just as the plane’s wheels were leaving the ground.

Though disappointed he could not fly at the air show, Alex Pepin did not give up. In September 1910 he and a crew were out at the fairgrounds again trying out the plane. It is reported that when the engine was started, four men were not able to hold the machine on the ground and a rope had to tied to a tree to hold it. By October, Pepin was still working on his airship, though a newspaper reported that parts of his previous plane were still being discovered from time to time around the field.

If Alexander Pepin did try again, there is no written record of it. He is next described as the local Houdini, performing magic and escape acts at a local wrestling match. In 1915 his wife died. After remarrying in 1917, Pepin moved to Bradley Beach where he worked as a clerk in a shoe store. Shortly after that he and his wife moved to Red Bank, New Jersey, where he continued working in a shoe store.

Alexander L. Pepin died in Kalamazoo, Michigan in 1954. Per his request, his body was buried in Mt. Carmel Cemetery in Asbury Park.

(c) Charlie Horner, Asbury Park Museum