Asbury Park – 150 Years of Change and Transformation: A Segregation Seashore

In 1871, in the wake of the Reconstruction movement following the Civil War, Asbury Park was born

Throughout much of its history, Asbury Park has been a segregated city…and nowhere were those often unwritten policies more in evidence than the resort’s popular beaches, boardwalk, seaside hotels and amusements. However, the story of segregation in Asbury Park did not start at the very beginning.

Asbury Park was founded in 1871 by New York City-based industrialist James A. Bradley. A devout convert to Methodism, Bradley was inspired to build a seaside resort community that adhered to the strict beliefs of the Ocean Grove religious camp meeting, located just south of what would become Asbury Park.

Christening the resort in honor of American Methodism founder Bishop Francis Asbury — and naming many of the streets in his planned community for Methodist pioneers and clergy — Bradley retained private ownership and full control of the beachfront, as Asbury Park quickly ascended to become a premier resort destination along the Jersey Shore.

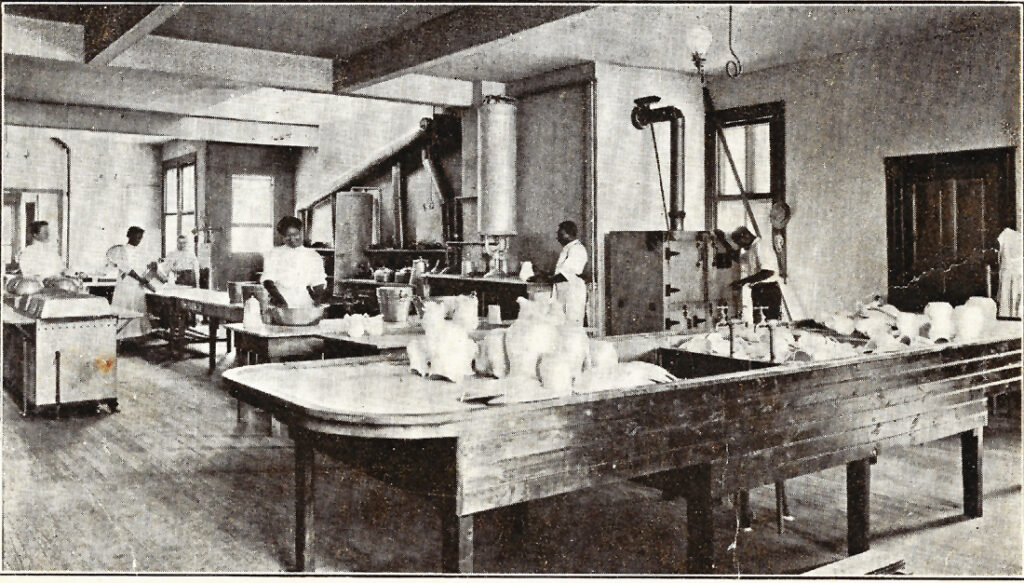

Even as thousands of white tourists flocked to the oceanfront, and in many cases relocated year-round to the fast-growing young community, a separate influx of Black people came seeking employment in the hotels, shops and restaurants of Bradley’s service economy.

As the Founder’s meticulously laid out plans became a reality, the place called Asbury Park was largely built on the labor of local indigenous people, Italian immigrants and African Americans who had fled the Ku Klux Klan’s reign of terror in the southern states — but those who worked in the grand beachfront hotels and establishments were largely relegated to living beyond the city limits in the area known as West Park (later the West Side of Asbury Park).

As Bradley laid out plans, the city of Asbury Park was largely built on the labor of local indigenous people, Italian immigrants and African Americans who’d fled the Reign of Terror of the Ku Klux Klan in the southern states. But those who worked to build and work in the grand beachfront hotels and establishments were largely relegated to living beyond the city limits in an area called West Park (later the West Side of Asbury Park).

In the early years, the largely African American employees of the huge beachfront hotels were, if not exactly welcomed, tolerated on the boardwalk and beach.

After work hours, black hotel employees found time for relaxation and recreation. The wait staff of each grand hotel formed fraternity-like bonds, often competing against rival hotels in sporting events like baseball games and foot races. However, as more and more people of color began frequenting the beach and boardwalk, Bradley’s attitude began to change.

Photo by Robert L. Bracklow, Alexander Alland Collection, Museum of the City of New York.

Courtesy of the Classic Urban Harmony Archives.

Bradley began getting pressure from hotel managers who said their guests were complaining about having to share the beachfront with black employees.

While Bradley at first feigned publicly to be a “friend” to people of color, his own newspapers began proclaiming that there were “too many colored people” in the resort area. The Asbury Park Daily Journal in 1885 ran an editorial saying “The colored people are becoming a nuisance in Asbury Park. … We allow them to vote, to have full standing and protection in law, but when it comes to social intermingling then we object most seriously and emphatically.”

With excursion trains bringing in additional black bathers as day trippers, the paper urged Bradley to ban people of color from the beaches.

With additional Black day-trippers arriving daily on excursion trains, the paper urged Bradley to ban people of color from the beaches — and by June of 1887, Bradley began restricting people of color from the beach. The Founder defended his actions in an Asbury Park Press article from 1887, stating that “I am free to admit that I wish to discourage the great number of colored people from coming here, not because I have any feeling against them as a race, but because I find that the patrons of the Park object to their great number.”

Backlash to Bradley’s Restrictions

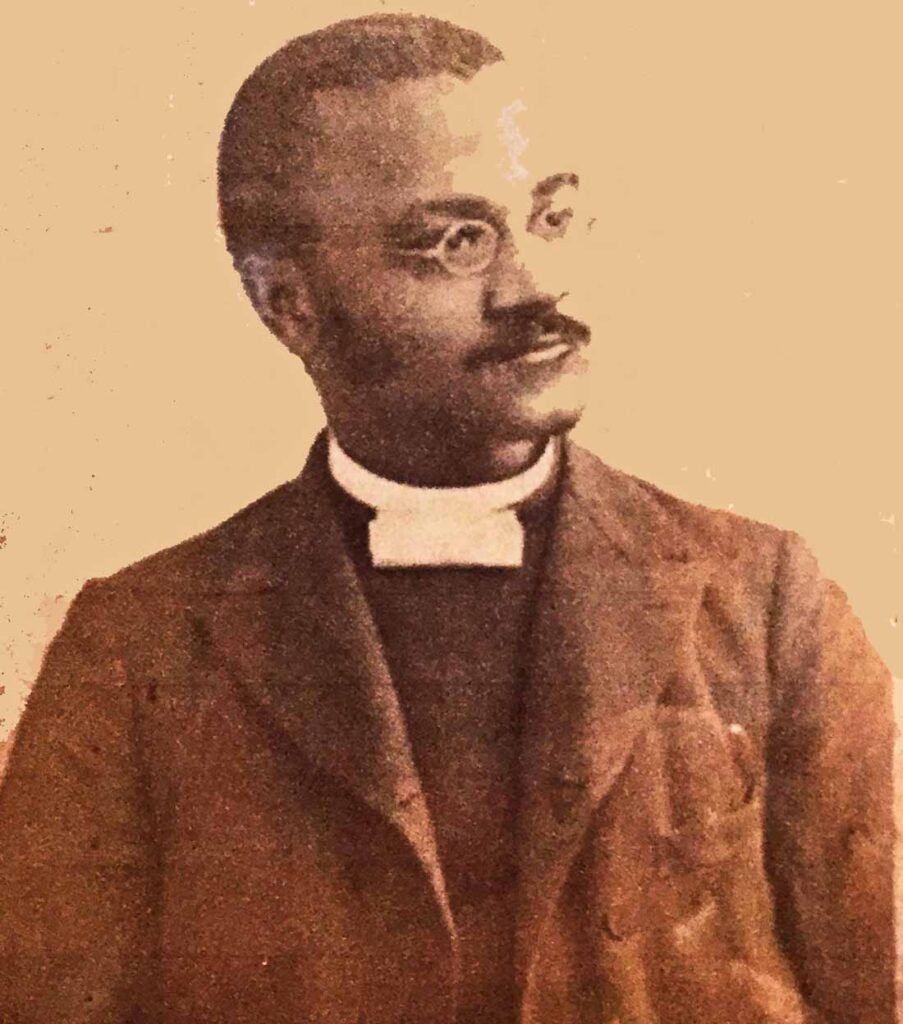

Bradley’s public stance drew immediate backlash from the residents of West Park. Reverend J. Francis Robinson, pastor of West Park’s St. Stephen A.M.E. Zion Church and a leading voice against segregation, firmly rebuked Bradley from the pulpit.

“We will take no dictation from James A. Bradley or any other white man on the face of the earth,” Robinson shouted. “Mr. Bradley and the white people object to the Negroes on the beach, where the free air of heaven blows and yet in the dining room they are willing to have the Negro sweat right over them.“

“Mr. Bradley might just as well try to hang his handkerchief on the horns of the moon as to keep out the black man from the beach,” the Reverend continued. “We fought for liberty and the salvation of this Union, and we are going to enjoy a piece of it.”

Robinson organized a series of “indignation meetings;” rallies in opposition to civil law distinctions on the basis of skin color. He created a form of protest at the beach called “the wade-in” — a precursor to the “sit-ins” that were popularized 80 years later in the 1960s — in which Black locals where they waded into the ocean en masse and lay upon the sand, in defiance of the official restrictions.

Since the beachfront remained Bradley’s private property, he could legally do as he wished — and he argued that restricting blacks from the beach was strictly a business-based decision. In those days, bathers would pay about 20 cents for rental of a bathing suit, towel and changing room before heading onto the beach — but for the next couple years, people of color were denied such bathing privileges in Asbury Park. Black people threatened to organize boardwalk protests, and Bradley responded by mobilizing his entire police force along the beach.

Bradley’s restricting people of color from the beach was met with outrage elsewhere in the region. On July 21, 1887, excursion trains arrived at the Asbury Park-Ocean Grove station from the northern New Jersey cities of Newark, Orange and Jersey City, and from Philadelphia to the south; all of them loaded with Black beachgoers. They met at Ocean Grove’s Great Auditorium where they celebrated “Jubilee Day,” singing spirituals and listening to speeches. Though none of the orators mentioned Bradley by name, their talk of liberty and freedom made clear what was on their minds.

Reverend J. P. Sampson, Chairman of the New Jersey Committee of the African Methodist Episcopal Churches said that “[even] the white people of Orange felt indignation at the reports of feelings against [people of color] and encouraged them to come. The crowd then spread out across the beaches of Ocean Grove and Asbury Park, the latter in defiance of Bradley’s rules. Many attempted to rent bathing suits and towels from the bath houses in Asbury Park but were turned away. Only a bad rainstorm broke up the protests. Local newspapers would downplay the incident, which was covered in more detail by the New York Times.

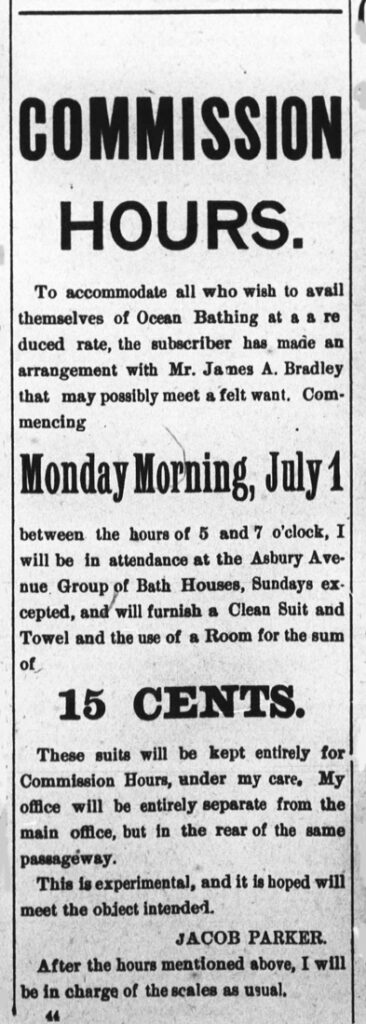

Clearly under pressure to resolve the “race issue” in the summer of 1889, Bradley came up with what he felt was a solution. He proclaimed the hours between 5 and 7 in the morning to be “Commission Hours” when people of color could use the beach.

Bradley thought his idea was brilliant, and his local newspaper wrote that “the innovation has caused general satisfaction among the colored people, and seems to provide a solution for the most difficult part of the colored question.”

Of course, the Commission Hours plan was doomed to failure, as apparently Black people didn’t want to go to the beach at 5 am any more than white people did — and during the first month after the plan was put into effect, the largest number of Black bathers taking advantage of the “solution” on a given day was no more than six.

Black bathers could only use one specific bath house, run by Jacob Parker, a Black bootblack who operated out of the Pavilion. There they could rent a changing room along with a bathing suit and towel specially marked “Commission Hours,” at a reduced rate of 15 cents.

A news article in the Fort Worth Daily Gazette, July 5, 1889 highlights the hypocrisy of the Northern population in its views of race relations.

“Even if Northern hotels and sleepers did refuse to take the medicine they insisted upon prescribing for their Southern contemporaries, in the pure and purifying waters of Coney, Long Branch, Cape May, Nantucket, Asbury Park and other resorts, all men would be free and equal among a people who so strenuously insisted upon such equality among other people.”

“This compromise (restricting Negroes to beach access from only 5 – 7 AM) does not admit the races into the water during the same hours and marks the towels lest by chance the white hand and leg should be dried on the linen that had performed the same service for the black hand and leg a week before. . . Vive la humbug.”

In 1890, James Bradley established a separate area for people of color, setting aside a strip of beach and boardwalk between First and Second Avenues for their exclusive use. He employed Black bath house attendants and lifeguards within the designated area, in which for at least the first year, Black bathers were restricted to the hours between 3 to 5 pm.

Having restricted blacks from much of the the beach, white hotel managers then began pressing Bradley to remove them from the boardwalk and the Pavilion – and in 1893, Bradley obliged, posting large signs forbidding Pavilion entrance to “members of the colored race.”

This was met with great indignation by the local black residents. A community meeting was quickly held in West Park, chaired by Reverend William H. Dickerson. About 500 people attended – among them James Bradley, who spoke in defense of his position in posting the placards. Sensing the anger in the room, the Founder considered a new approach.

The following year, Bradley changed the wording of the signs he’d hung in the pavilions. Instead of barring black individuals from using the pavilions, the signs were changed to bar ‘employees of hotels’ from being in them. The change in language was done to as to create a race-neutral rationale for excluding Black people from the pavilions.

The segregated Second Avenue Beach arrangement continued until 1915, in spite of the constant protests of hotel managers in the heart of the hotel district. By that time, James Bradley had divested himself of his waterfront holdings; the West Park neighborhoods had officially been annexed by the City of Asbury Park, and “friend of the West Side” Clarence Hetrick had begun his long tenure as Asbury Park’s mayor. Eventually, the protests and petitions of the Second Avenue hotel managers took effect, and the bathing area for people of color was moved to a spot south of the Casino, at the foot of Wesley Lake.

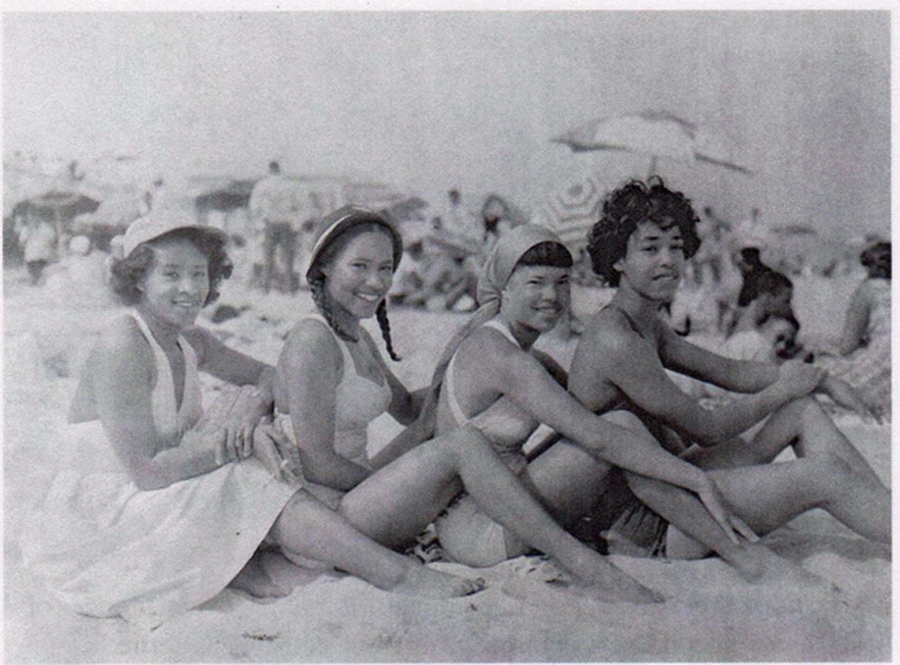

When the original Casino burned down in 1928, a new larger Casino was built at that location, along with a Power Plant structure that effectively blocked white beachgoers’ view of their Black fellow bathers. This bathing area for people of color was a particularly rough area of the surf called the Mud Hole — sometimes variously referred to as the Ink Well, and, according to one individual’s recollections, the “pipe” beach.

The Mud Hole remained the only place in Asbury Park where black people could swim through the 1940’s and possibly into the 1950’s. As local jazz artist, Eddie Watt recalled to his son Robert Lee Watt, “When I wanted to swim after work on those hot summer days I was not allowed to go into the swimming pools down at the beach, even though the sign on the building said in great big letters, “PUBLIC BATHING.” Those crackers laughed as they told me, “Hey, boy, why don’t you go on over to the colored beach and swim – but you might drown trying ‘cause there’s lots of sewer pipes in that water.”

For years it was said that wastewater from city sewers flowed from the pipe that let out into the ocean in front of the colored beach. While some have disputed this, it was and still is the perception of many of the city’s black residents. The actual explanation for the pipe is that it was wastewater from the Natatorium, and not sewage.

Discouraged by their treatment at the Asbury Park beach, many Black residents would in later years prefer to swim at the beach in nearby Belmar, which had abandoned the concept of segregated areas in 1928 and had opened their entire beach to all races. While that tradition has faded away in recent years, the practice of Black bathers favoring Belmar’s beach over that of Asbury Park remained in place for decades.

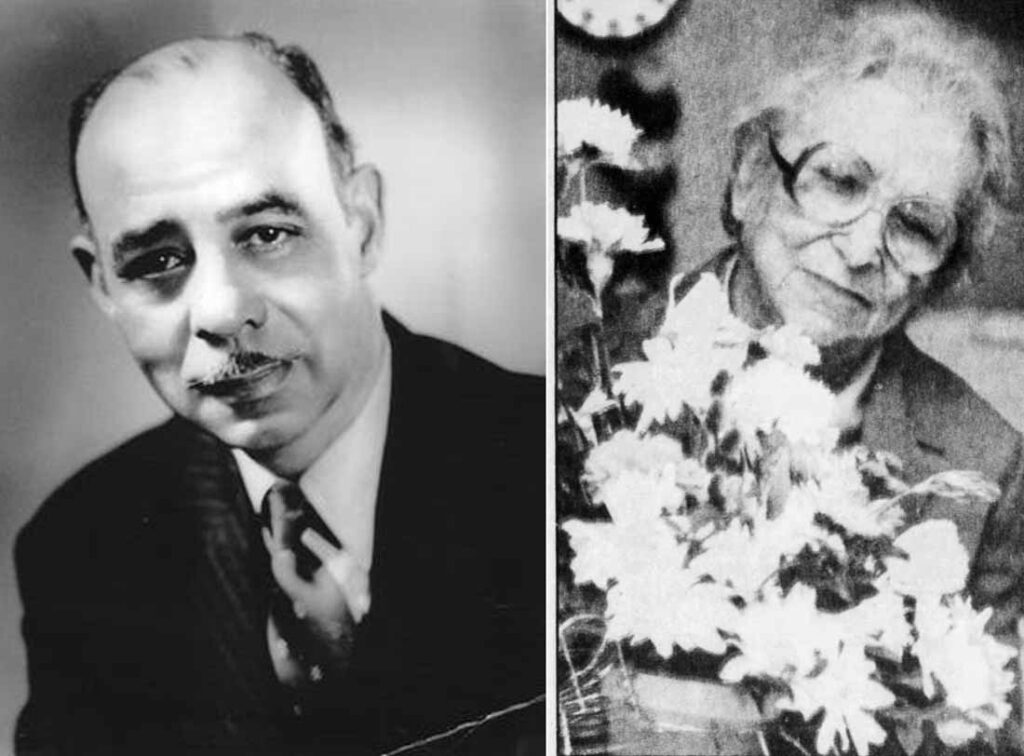

Black artist and future Civil Rights advocate Lorenzo Harris Sr. arrived in Asbury Park, having found a hostile reception to his presence on the beach in Atlantic City. The only way that the creator of spectacular sand sculptures could practice his trade on the Asbury Park beach was to pretend to be an Arab, rather than a Virginia-born and college educated African American. Eventually abandoning the ruse, Lorenzo Harris would go on to found the local chapter of the NAACP, serve as an officer of the original Asbury Park Historical Society, and inspire his physician son Lorenzo Harris Jr. to become the first person of color elected to Asbury Park’s City Council

In 1934, Lorenzo’s wife Kathryn Harris was involved in a dispute with the ticket booth operator of the boardwalk merry-go-round, when they refused to sell her young niece a ticket because of her race. When the operator forcibly removed the child from the merry-go-round, a physical altercation occurred, and the police were called.

Lorenzo and Kathryn took the owners of the merry-go-round to court and pressed charges. The matter was settled when the merry-go-round owners took out a half page ad in the local newspaper, stating it was not their policy to discriminate. From that point on, boardwalk concessions were integrated.

Having a public stance against discrimination did not bring an end to the issue. People of color were still outright turned away from boardwalk establishments such as the Monte Carlo Pool (built by movie theatre magnate Walter Reade) and Natatorium; refused service at restaurants, and seated in the balconies of the Reade-owned theatres. Most instances of discrimination went unreported.

In 1942, the play “Native Son” was running at the Paramount Theater. It starred nationally acclaimed black actor, Canada Lee. When Lee, another black cast member and Lorenzo Harris objected to not being served at a boardwalk restaurant they were assaulted. Two restaurant waiters were later charged.

By the 1950s Asbury Park was undergoing transformation.. The Garden State Parkway which ran 172 miles north to south through 10 counties and 50 municipalities near shore communities opened in 1954. The postwar era saw more Americans owning cars than ever before, and the Parkway provided a direct route to Asbury Park for working class families.

After years of Depression and a World War, Asbury Park was again a favorite summer destination, with its rides and amusements, including paddle boats and swan boats on Wesley Lake, and even pony rides on the boardwalk. While it was a different sort of resort than the one that beckoned well-to-do city folk in the Gilded Age of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Asbury Park was still perfect for a day trip, or even a vacation of a week or two.

The 1960’s and Beyond

Black people, however, continued to find themselves unwelcome at the boardwalk pools throughout the 1960s, even as those pools (the last of which closed in 1971) entered their final years of operation. Claire Garland, the director of the Sand Hill Indians Historical Association and Asbury Museum advisor, recalls her mother marching on the boardwalk with others in the early 1960s, to protest discrimination on the waterfront.

At the same time, amusement centers like the Palace complex and the Casino relaxed their restrictive practices of decades past — and by the late 1950s and 60s, local school-age children were offered strips of ten tickets for a dollar to attend Wednesday morning double feature movies at the city’s movie houses; a program that included live entertainment during the intermissions.

By the 1970’s, Asbury Park had begun to decline. Businesses downtown struggled. The great majority of businesses on the Westside were lost to the Civil disturbance in 1970. Nothing was done to rebuild. Hard times fell on the City, east and west.

The 21’s Century

While Asbury Park’s “comeback” in the 21st century has seen a more diverse city emerge from the economically depressed and largely abandoned “ghost town” of the 1970s, 80s and 90s, the waterfront did not see a large number of young Blacks, Hispanics and Haitians acquiring employment in customer-facing Boardwalk jobs until very recent years.

The first new businesses to open in the early 2000s were not very receptive to the presence of Blacks on the boardwalk, nor did many of those businesses tend to employ many persons of color. Since then, boardwalk business owners have come to see the value in providing employment opportunities for the residents of the greater Asbury Park area. Because most of the jobs are seasonal, however, the positions tend to attract younger people, rather than adults who desire year-round employment.

Today, the youngest of the generations of beachgoers are likely oblivious to the history of Asbury Park’s segregated seashore, a history that was largely suppressed in the official record for many years — but for those with an interest in building a stronger, more truly diverse community from the lessons of an often shameful past, the beaches and boardwalks resonate with the righteous indignation, the chants of protest, and the summertime laughter of all those who fought for dignity, rights, and respect in this city of sandcastle dreams.